Date and place

- February 11th, 1814 west of Montmirail, Marne, Champagne, France (now part of the Grand-Est region).

Involved forces

- French army (16,300 men), under Emperor Napoleon the First.

- Prussian and Russian armies (32,000 men), under General Johann David Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg and Prince Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken.

Casualties and losses

- French army: approximately 2,000 dead or injured.

- Allied army: about 4,000 men dead, injured or prisoners.

Aerial panorama of Montmirail battlefield

Following the Champaubert victory on February 10, 1814, Napoleon wasted no time in implementing the plan he had devised a few days earlier at Ferreux-Quincey

Napoleon chose to march on Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken

Marshal Adolphe Edouard Mortier, who was staying in Sézanne

For their part, the two allied generals, who had not received orders from Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher to join forces at Montmirail until they had reached their respective milestones, turned back and found themselves, on the morning of the 11th, Yorck at Viffort

Both Yorck and Osten-Sacken came up against Nansouty's troops, who, after having disposed of the Russian garrison at Montmirail without too much trouble, had positioned themselves across the roads leading from there to La Ferté-sous-Jouarre

As a result, Yorck wanted to retreat to Château-Thierry and sent an emissary to Sacken offering to join him there. Sacken, on the other hand, believed he could make his way through the French to Bluecher. Intelligence from a "reliable source" had convinced him that he had only a small contingent in front of him, and he had no idea that Napoleon himself was in command.

Faced with the Russian general's resolve, Yorck had no choice but to set off to lend him a hand, but his departure, around midday, was so late, and the appalling state of the roads so delayed, that he would not arrive until Sacken was already in full rout.

Start of the battle

On arriving in sight of Marchais

At around 11 a.m., Sacken captured the hamlet of Marchais and the Chouteaux farm

For his part, Napoleon left Montmirail around 10 a.m. with reinforcements to reach Nansouty. Some 10,000 men and 20 cannons now faced Sacken.

While the cavalry observed each other on the French right wing, fighting raged at Bois Bailly

But it was around Le Tremblay

The numerical superiority of the allies finally got the better of the stubbornness and courage of the French, who withdrew to Le Tremblay at around 2 p.m., having seen their numbers halved.

The situation became critical for Napoleon when scouts began to report Prussian contingents at Fontenelle

Fortunately for the French, around 3 p.m., Marshal Mortier finally reached the battlefield. He brought with him General Claude-Étienne Michel

The bulk of the Michel division was immediately sent to reinforce the right wing in anticipation of the imminent arrival of the Prussians. A few regiments reinforced General Ricard's division. The rest were placed in reserve.

The French counter-attack quickly began.

French counter-attack

To the south, Marchais-en-Brie was attacked again by the Ricard division, supported to the north by two battalions of the Old Guard commanded by Marshal François-Joseph Lefebvre and General Henri Gatien Bertrand

Earlier, at the head of General Friant's 1st Infantry Division of the Old Guard, Marshal Michel Ney had stormed the Greneaux farm. The charge, on foot and bayoneted, overcame a formidably entrenched enemy who had so far victoriously resisted all shocks.

While Ney attacked Les Greneaux, several cavalry charges undermined the rest of the Russian corps occupying the crossroads between the Paris and Château-Thierry roads, in front of La Chaise. It was soon pushed back west to La Meulière.

The Russian center was now separated from the right. General Pierre d'Autancourt's (known as Dautancourt)

Sacken then decided to attempt a junction with the Prussians, whose vanguard was reported at Fontenelle around 3 p.m., by first withdrawing his two corps to the Haute-Epine and then marching them northwards. The maneuver was a delicate one, with soggy ground making it difficult to move artillery. It also exposed the Russian flank to French infantry fire and enemy cavalry charges. Their combined action disemboweled several Russian squares between the Bois de Courmont

Prussian arrival and epilogue

When Ludwig Yorck finally came to the rescue, however, he did so with great caution. He had left his heavy artillery with some of his troops at Château-Thierry, and was in no hurry. As a result, it was not until around 4 p.m. that he attacked the farms of Grange-en-chart

However, his slow irruption endangered the Friant division, which had reached La Meulière and was in danger of being cut off.

That's when Emperor Napoleon sent in his reserve and the rest of the Michel division under Mortier's command. The Prussians found themselves under heavy crossfire. Their first line fell back on the second, then, after a vigorous assault on their flank, the whole was pushed back towards Presle, where Yorck was able to organize a Prussian counter-attack that brought the French to a halt.

It was now eight o'clock, night had fallen and the fighting had ceased.

The battlefield was in French hands, with Yorck retreating to Château-Thierry by the direct route, and Sacken on the roads between Haute-Epine and Montcel [Mont Cel Enger]

The outcome of the battle

With this latest defeat, the day after Champaubert, the Atmy of Silesia suffered a major blow. Beaten twice in two days, despite overwhelming numerical superiority, the Russians and Prussians suffered a terrible humiliation that sowed the seeds of discord between them.

The victory at Montmirail was still not the decisive success Napoleon was looking for. Its effects were limited by the inability of Marshal Etienne Macdonald, whose troops had retreated from Epernay

The French had 2,000 men out of action. The Allies lost between 3,000 and 4,000 men, dead, wounded or prisoners, and around 20 cannons. Above all, they demonstrated the mediocrity of their command, Yorck showing himself to be soft and

indecisive, while Sacken failed to take advantage of the numerical superiority he had at the time of his morning attack.

As for the soldiers, while the veterans of the Guard once again demonstrated their exceptional value, the conscripts, the famous "Marie-Louise", with equipment as basic as their military training, won the admiration of their glorious elders.

On the evening of the battle, the imperial headquarters moved to the hamlet of Haute-Epine

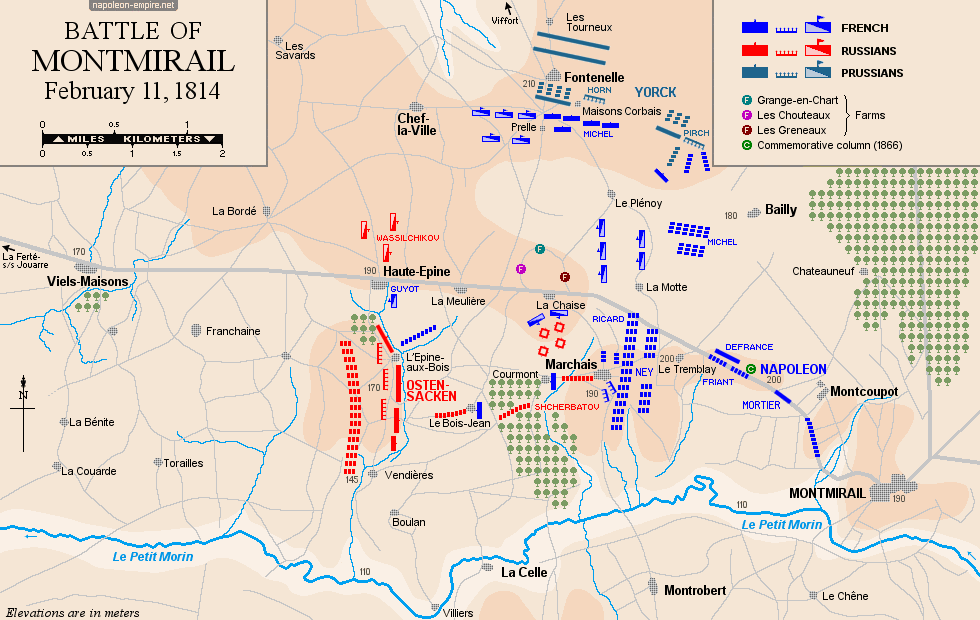

Map of the battle of Montmirail

Picture - "Battle of Montmirail". Painted 1822 by Emile Jean Horace Vernet.

In many accounts of the battle, starting with the bulletin of February 12, 1814, the place known as Ferme de l'Épine-aux-bois was actually the Greneaux farm.

Just beyond Montcoupot, on the border of the Aisne and Marne departments, a column

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814

Display the map of the Campaign in northeast France in 1814